Groups

Brandon and Hamsteels Local History

About the group Project groups in the Deerness Valley

Created 14 March 2013

history group |

||

|

At my first day of work, I caught the ‘pit bus’ from where I lived in Crook to Brandon Pit House Colliery at approximately 7am. I was met at the pit by the Training Officer who showed me around the canteen, then to the baths, where I was given a locker in what was the ‘clean’ end, then to my locker in the ‘dirty’ end. This area was where your work clothes were to be kept. After a tour of the colliery, the Training Officer took me toward the workshops. We were met by the Engineer, let’s call him Jack, who greeted me with the words “Come with me”. He asked me if I could ‘solder’ and when I said “No”, he showed me how to solder two contacts together. After the demonstration, he gave me a box of contacts to be soldered into pairs. He then proceeded to leave me with the parting words ‘I’ll come back later to see how you are getting on’. My immediate thought was, if this is what working is about, I do not like this one little bit. During my first day at the pit, another apprentice electrician started work. We will call him Jingles (this was his nickname) and we became the very best of friends and mates. The older apprentices and qualified electricians had a lot of time for us and taught us how to be good electricians for future life. Just before Christmas, Jack would send Jingles and me across the fells looking for berry holly. We always loaded ourselves up with the holly until we couldn’t carry another sprig and beaming with pride we would return to Jack’s office. He would always shout at us ‘That’s not enough, go and get some more’. We used to think he supplied the county with holly but later in life we were told that he used to give some to the Aged Miners homes. Looking back, Jack was a good boss, really – if you did wrong, he told you. But he never held a grudge. This photograph shows the reclaimed site of Brandon Colliery today. Pit House colliery was nearby. |

history group |

|

|

The third digital story contains memories by residents of Brandon of the region's traditional Big Meeting Day, the Durham Miners' Gala, shared with young people growing up in the village after the heyday of mining in County Durham. The memories are accompanied by photographs of the Miners' Gala in 2012, taken by the young people.

|

Sandra Brauer |

|

|

The second digital story shows extracts from work undertaken by residents of Brandon, who came together for the first time as part of this community project to share their memories of living in so-called 'Category D' mining villages and research their history.

|

Sandra Brauer |

|

|

Dear all,

I am pleased to finally be able to upload the digital stories produced from all the work you have done with Dorothy over the course of this project. This had not been possible previously due to a few technical hitches. I hope you are equally as pleased with the results of your hard work - and deservedly so. The first of three digital stories showcases work undertaken by Hamsteels Local History Group. Best, Sandra Brauer Britain from Above Activity Officer (England) |

Sandra Brauer |

|

Copyright English Heritage (Image number EAW043753) |

history group |

|

Robert wrote vividly about the old house he grew up in as a child in Esh Colliery, with its large black range, and no indoor lavatory – just an ashpit across a dirt track which “passed for a road”. The house had a long front garden which was used for growing vegetables. The family also had an allotment where hens were kept, and during the Second World War, they also kept a pig. Around 1956 the house had an outside toilet built in the back yard. These houses have since been demolished, and the site opencasted for coal, “bringing an end to a frugal but happy way of life”, as Robert described it. He went on to describe the new house he moved to on the Hamsteels Estate, which had just been built and still smelt of paint when he moved in. It had an upstairs and downstairs toilet, a bathroom and central heating. The new houses had some problems, one being the electric heating which was very expensive, so the council as landlords put in solid fuel stoves. Robert’s experience of moving from a colliery house to a new council house was typical for many other people in the Durham coalfield area in the 1960s and 1970s. Peterlee, seen in the other picture, was intended to re-house miners in new houses with modern facilities. Another member of our group lived in Peterlee in the 1960s, when there were a lot of houses still being constructed. Dorothy Hamilton, Group Leader |

history group |

|

.jpg) The headquarters of the Durham Branch of the National Union of Mineworkers is a very impressive red brick building situated at the northern edge of the city. It is clearly visible from the train as it leaves Durham, southbound, across the impressive viaduct which straddles North Road. Passengers may well be distracted by the view of the castle and cathedral if seated on the opposite side of the train but others may well wonder about the building with the green dome. It was designed by H. T. Gradon a local builder and architect and the building contractor was J. Pattison of Gateshead. It was opened on 23rd December 1915 and is now a grade II listed building. In the grounds stand four marble statues, also grade II listed. The statues are a tribute to early pioneers of the Union, Alexander McDonald, William Hammond Patterson, William Crawford and John Forman. The statues were originally situated at the office of the old Miners Hall in North Road. Anyone connected with the mining industry will know this building simply as “Red Hills” although that is actually the name of the area in which it is situated. The name is said to have been coined after the battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346 when the hill was said to have turned red with the blood of the defeated Scots army. Enter the imposing portal of “Red Hills” and one cannot help but be impressed by the quality of the workmanship, from the marble flooring, the grand staircase and the solid wooden doors and wall panelling and the stained glass windows. Behind the staircase there is a very grand auditorium capable of seating a large number of union representatives who attended the “Miners’ Parliament”, one representative for each pit in the Durham coalfield which, at its peak, numbered some two hundred. When I worked there in the early 1960s there were four agents who were responsible for the running of the various sections of the union. They were assisted by around twenty staff, many of whom spent most of their working life at Red Hills. The agents were voted into office by the pitmen. On the same site as the headquarters, were houses for the agents. On the right of the front entrance was a small room which served as a post room and telephone exchange for the building. The ground floor contained offices of the compensation and finance departments. Upstairs the General Secretary had his office, along with another section of the compensation department and the treasurer’s office. I enjoyed my time working at Red Hills. I met some very colourful characters and was one of only five females working in a very male environment. Consequently the ladies cloakroom was some considerable distance from the front of the building, tucked away behind the main chamber. I do remember a friend and colleague, who suffered severe sickness during her pregnancy, regularly having to make a dash for the men’s toilet which was next door to her office. Most of the offices were heated in the winter with a coal fire. No central heating for this building in those days. This stark description of the layout belies the dedication and commitment of the people who worked there. Most had lived within the mining communities and were familiar with the particular language of the pits and the pitmen, not to mention the famed camaraderie and closeness of the pit villages. Even after 1947 and nationalisation the pits were a dangerous working environment. The compensation department dealt on a daily basis with the consequences of this danger, the accidents, major and minor, and the long-term health issues resulting in pneumoconiosis and other lung complaints. The once great industry of the Durham Coalfield is no more. The pit heaps have gone and the countryside has reverted to its former beauty. Some of the old pitmen who left the mines to work in factories were delighted to be employed in light, airy buildings but there has always been, for some, the regret that the comradeship and community spirit that existed within the mining communities is gone. I’ve heard more than one miner say that given the chance, they’d go back into the pits. Anne Photograph of Durham showing Redhills Copyright English Heritage (Ref: EAW005522) |

history group |

|

|

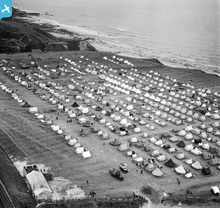

Crimdon Holiday Park

A Trimdon man named Mr Lowes bought some land from Mr Collingwood a local farmer who owned Hart Dene and Beach Bank fields. Mr Lowes built wooden huts to hire to people looking for work at local collieries. These were people who had travelled from places such as Wales or Cornwall. Crimdon Dene camp started sometime in 1946 with ex-army tents. The picture also shows round the side of the camp a small number of caravans. The photo shows a small wooden building, could this be a shop? We can also see a brick building, maybe this could be a toilet block? Looking at the photo we can also see people walking from underneath the railway bridge possibly from the buses that are parked there. In the 1950s the site was filled with Aluminium Altents. These had a table, four chairs and four bunks. Blackhall History group writing on the Durham County Council website durhamintime noted that they were shaped like African round huts and were made of aluminium sheeting which made them hot in summer and cold in the winter. By about 1955 caravans took over the site. I can remember in the 1960s friends of my mother, who had a caravan at Crimdon, asking if I could go and spend the weekend with them. I found this very different to what I had done before. My friend and I slept on the top bunk with her mam, dad and brother on the bottom bunk (which had turned into a double bed) her sister and her friend slept on the other double bed which during the day was the table. My friend’s dad had to climb into bed with the door of the caravan open then lie in bed and close the door, this did look very funny. On the Sunday morning my friend and I went outside and watched the Jazz Band come round the caravan park. Later we went back to the caravan and had our dinner before we packed the car and came home. What is different now is we would not be allowed to pack a car or I suppose even a caravan the way we did then. Rhoda |

history group |

|

This photograph taken in July 1948 of Durham, shows the north end at the top of the picture, at the top left we can see Redhills, a building owned by the National Coal Board. We focus then on the County Durham bus service garage. The building to the right of this is the Durham County Hospital. This hospital was erected on an elevated point in the north of Durham which does not really give you that impression from the photograph. It is a spacious building made of stone and was built with subscriptions and donations from wealthy local people. It was built in the Elizabethan style in 1850s at the cost of £7500 with a forty two bed capacity. It was the main general hospital of County Durham when this photograph was taken but this status changed in late 1948 when it became the main orthopaedic, accident and emergency department and trauma hospital for the county of Durham. Immediately in front of the hospital we can see the viaduct. Durham train station is not shown but is to the left of this picture. At the extreme top right we can see Dryburn Hospital named after the area where it is situated. This is the former site of the of Durham city gallows. In July 1594 John Boste one of the Roman Catholic martyrs was hung drawn and quartered here and his innards were thrown into a nearby burn which, so the story goes immediately dried up, hence the name Dryburn? Dryburn Hospital, a one story building was built in early 1940 mainly to take the large number of war wounded including German prisoners of war coming back from Dunkirk during the Second World War. The casualties would arrive at Elvet train station and be transported up to Dryburn at night so as not to cause too much distress to the people of Durham. When the National Health Service was established in 1948 Dryburn became the General Hospital of Durham as well as becoming a training school for students wanting to gain State Registered qualifications. It was also affiliated to the R.V.I. and Newcastle university Medical training school which allowed Dryburn to be used as part of medical students training. Kath |

history group |

|

|

Closure of the Coal Mines.

One of the pictures is identified as Vane Tempest colliery in 1971. This is one of the coastal pits that were situated along the N.E coast. These pits as well as working the inland seams of coal could also exploit the seams that ran out under the North Sea. It was to one of these coastal pits that I was transferred to in 1975 and the layout of the colliery in the picture is typical of most colliery sites. Running parallel with the coast is the main road which runs past the colliery and continues along to the harbour area. In the centre of the picture are the two shafts which all collieries were bound by law to have to work a coal mine. One shaft would be used as a ventilation shaft where air would be drawn down the shaft (downcast) and the other would be used for drawing the air out of the pit (upcast). Also in the picture are the railway trucks that would be used to transport the coal to various power stations throughout the country. We can also see a number of gantries that would have been used for transporting the coal from the shaft to probably a washer and from there to the bunkers where we can see the trucks ready to be filled with coal and then transported by rail to a power station or to where the coal was needed. Noting the position of the parked cars it would seem that the pithead baths were in between them as we can also see the tall chimney which would have served the boiler house which would have supplied the hot water for the baths. Looking at this picture takes me back to 1975 when my own inland colliery was running out of reserves and the workforce were given the chance to relocate to another colliery either inland or to some of the coastal collieries like the one I am looking at. We were taken to visit some of these collieries and I opted to go to a coastal colliery where we were assured of a good working future. Most miners lived in the village where they worked and generally lived in a colliery house but for other miners not living in the pit village they were quite used to using the bus as a means of getting to their place of work. So when the time came to travel to the coastal pits all miners were obliged to use the transport provided by the Coal Board. Going to work by bus involved a longer time out of the house and also after a time we would pick up other transferred miners on our route. So our new colliery would employ miners from all parts of Co Durham. We quickly found out that we would be expected to work a four shift system which most people found difficult to get used to as they had been used to the shift work at their former colliery. At my former colliery I had been a coal hewer and had worked a two shift system. At the new colliery we were employed on development work which was suited to the four shift system. Instead of walking down a drift to our place of work we went down the shaft in a three deck cage and were then taken inbye in carriages pulled by a diesel locomotive. Our task was to drive a drift between two seams of coal and this was achieved by drilling into solid stone and blasting a way forward. The resulting stone from this shot was loaded onto a chain belt by means of an Eimco shovel loading machine. In time we were given many different tasks and used a variety machines which made the tasks a lot easier. We had worked at this new colliery for nearly ten years when we went out on strike over pit closures and after a year on strike we went back to work only to be told our own colliery was to close and so after 31 years working down the mine we were given redundancy payments and left to our own means of getting employment. I was extremely lucky by getting a job at a local factory and then finding a job as a school caretaker which lasted until I retired in 2005. T.G.N. Photo Vane Tempest 1971. Copyright English Heritage (EAW212120) |

history group |

|

|

The Drill Hall at Hamsteels

The plan for the Drill Hall at Quebec for the owners of Hamsteels Colliery was approved by the council on March 28th 1907. The hall was used by the villages and during the war as a meeting place for troops. By the late 1920s, early 1930s everyone was feeling the effects of the depression which affected the whole of the country. Life was hard in mining communities as most jobs were connected with mining in some way or other. In some more affluent areas of England people got together to try and give some help to these depressed areas. People like Deptford choose to adopt places like Ushaw Moor to try and give assistance to people in need. The people of Sevenoaks Kent adopted the Drill Hall at Quebec. As with other adopted places the help that they were given was with food, clothing and blankets. Sometimes a small committee of people from Sevenoaks would travel to Quebec make sure the help they were giving was the right help. This created a good feeling between the two communities. A map of the area shows the Drill Hall re-named Sevenoaks Hall. The name was kept till the 1976 when the hall became grant aided and changed its name to Quebec and District Village Hall. Rhoda |

history group |

|

|

Ushaw College

The aerial photograph we see of Ushaw College is deceiving because it does not give a true bearing on the position of Ushaw. It stands on a hill at least 50-100 metres above the Deerness Valley, Esh Winning the Browney Valley and Langely Park. Looking at the photograph you would certainly think it was a flat area. The college itself is situated about three miles from the magnificent Cathedral City of Durham on the roadway from Durham to Bearpark. The college was founded in 1808 and its main purpose was training of men and boys as priests in the Roman Catholic religion. At one time 400 students studied there, and there were thirty professors teaching them. Most of the students who studied at Ushaw entered at about 11 years of age and passed out as a priest at 26-27. The students spent a lot of free time walking around the valleys in groups to Esh Winning, Ushaw Moor and would visit the pubs and the cafés in the local villages. On leaving school at fourteen I got my first job, and that was working at Ushaw College as a pantry boy/junior butler. My main job was working in the parlour setting out tables for meals, serving food and clearing away all crockery and then washing it by hand, no dishwashers in those days, and the general work in the parlour. My reason for starting work at Ushaw College was, I did not want to work in the Coal mines as this was a dangerous and dirty job. It was the main industry that employed most men and boys in our area. There were ten different coal mines in a radius of five miles of my home, a street called Railway Terrace. This made it easy to get to work, most men walked to the place they were employed at or used a bicycle to get there. The journey would take no more than half an hour and a lot less to some of the surrounding pits. It was a lot safer travelling the roads in those early days as there was not the volume of traffic using them. Public transport was used more, there were more buses to be seen running than there is today. Buses were in great demand, people did not own as many private cars as we see on the roads today. I travelled to Ushaw College to work on my bicycle and this took about half an hour. We started work at 6-30am till 2-30pm, and 1pm till 8-30pm.The work we carried out did not change much, the same routine every day as many domestic staff did in those days. During the holidays or vacations as they were called in those days when the students were away from the college we had different jobs allocated to us. One of the jobs we performed was cleaning the silver. This was quite a task, as there were lots of altars and chapels displaying vast numbers of candles sticks, crosses, flower vases, which keep you going. We also cleaned the carpets in the many rooms on the different floors in the college - there were hundreds of these around the college.We carried them down the stairs and outside on to the grass and beat the dust out of them with a bamboo bat shaped like a tennis racquet. One job I recall to mind and smile to myself many times when I think about it was a task set for me in St Cuthbert’s Chapel. It was to clean the lectern known as the Ushaw Eagle. As you can see from the photograph of the lectern it is a beautiful work of art. Well out came my dusters and cleaning cloths and a tin of Brasso. This I opened and gave the lectern a liberal coat of Brasso. This in time dried in to the feathers and the rest of the Pugin designed artefact. Instead of looking like an eagle it was more like a white dove, Duggan’s design. It took two whole days to clean it up and bring it back to its original splendour with several pails of warm water and soap. Ushaw College is a magnificent place to visit. The staff and workmen working there covered most of the trades and skills and were nearly self sufficient. The domestic staff were comprised of chefs, cooks, kitchen staff, bakers, scullery maids and laundry personal. Seamstresses and many others were employed in the making of cottas and cassocks for priests and students, and in the early days men’s suites for most of the personnel. At that time there was a contingent of women and girls who had come over from Ireland to work at Ushaw College. They carried out the work of maids in the student dormitories. Most of the trades were covered- Painters, Bricklayers, Stone masons Electricians, Joiners, and even a chauffeur. Milk, meat, potatoes, and many other produce came from the college farm. There was also a large garden, an orchard, and several glass green houses, with several bee hives dotted around growing food served in the college. This was the way the college was run and the way of life for those students aiming to take up the priesthood. My time spent working at Ushaw College was not a long one, but I enjoyed my time in the surroundings and the work we did. It is a sad situation the Catholic Seminary at Ushaw College finds its self in today. After 202 years training priests it closed its doors in 2010. The remaining number of men, 22, have moved on to different locations hoping to fulfil their training as priest in the honour of God. Due to the endeavours of the trustees, and diocese of Hexham and Newcastle working with the University of Durham, Ushaw College is once again alive to the sound of student voices, of course the students and books are different, but it is the reawakening of history keeping education going in a different form but keeping a marvellous place for learning alive and fruitful. Syd |

history group |

|

|

The County Hospital is shown at the top left of this picture of Durham.

|

history group |

|

I am very happy that all Britain from Above website users are now able to read all your interesting and moving memories in this group. From having met you during the project sessions, I know about the hard work and dedication that went into creating them. I do hope you will continue to research the fascinating history of the beautiful part of the country you live in, with as much meticulousness and pride of place as you show in these short extracts that only make you want to find out more. This is why I have uploaded one of the images of the Aerofilms collection that show the Miners' Gala in Durham in 1953 - a big event as you remember it in your memories below. The very best, Sandra Brauer Britain from Above Activity Officer |

Sandra Brauer |

|

|

In 1970 I was the Mayor of Durham and because of this my wife and I were invited to join Harold and Mary Wilson at the Miners’ Gala. My function was to give a Civic Welcome to this most important event. All of us came together at the ‘Royal County Hotel’ in Old Elvet and Harold Wilson and I led a parade of dignitaries, political and mining Industry, to the hustings where all the speeches were to be made. At that moment, it started to rain – surprise, surprise. I hoisted an umbrella over myself and Mary Wilson. I’m sorry to say the drips fell on Harold who said ‘I wish you adjust your umbrella. The drips are falling in me!’ I was embarrassed!! I liked Harold W. He was a great man. The secretary of the mineworkers was supposed to introduce me to give a civic welcome. He came on the platform and reached for the microphone but fell off the platform and was not seen again. Immediately, someone else seized the microphone and began a half hour diatribe on why the National Union of Mineworkers should go on strike against a Tory government! I never got to give the civic welcome! |

history group |

|

|

Olive: The Miners’ Gala I have lived in Langley Moor and Brandon all my life but not in a mining family. My family were haulage contractors in my early years, then we had a car demolition and scrap iron business. In the 1950s I drove taxis and in the 1960s I was involved with my husband’s taxi business. My mother would take me and two sisters to the top of North Road to watch the banners and bands march from the top of North Road in the city. I have been once to the Miners’ Gala service in the Cathedral and remember it to be a very moving service. I know many families who worked at the local collieries and who met at the race course and picnicked each year. I also know families who had moved to Doncaster, Nottingham and Yorkshire collieries when the Durham collieries had closed down and who came north for Gala Day by buses to meet relatives and friends left behind. When I was doing taxi work, we were busy taking folk to and from our area to Durham. The pubs were open all day! I have seen staff brushing broken glass bottles out of the door ways but everybody seemed to have a good day. I am told visitors sat about on the grass to listen to the speakers - Labour MPs and other Union leaders. |

history group |

|

|

When the residents in Langley Moor were informed that homes and properties were to be demolished, many were shocked and sad to be moved to Meadowfield or to Brandon. However they were delighted to go into a new house with bath, hot water and water toilet, too. It did not affect me. My father had a scrap metal business, he also bought cars to demolish, sold the parts to keep other cars on the road too e.g. batteries, tyres and many other engine parts. Some families still missed Langley Moor shops and came to Langley Moor for a long time. The Co-op built a grocery branch in Brandon at the entrance to the new Brandon shopping centre. The people in the houses by the Saw Mill Lane had a long way to carry shopping. A lot of people still went back to Langley Moor for shopping. As time went on, 3 rows of colliery houses in Littleburn were demolished. Langley Moor shops lost many customers due to the Category D era. Some of the High Street Houses are still there, some had alterations fitting baths and toilets by altering 2 houses into 1. New Brancepeth had many changes too, but still has a reasonable village feeling today. Meadowfield has had new estates built as Langley Moor had, too. Like many areas grocery shops are few now, as the modern supermarkets have taken over which has made another big change to life in Category D areas again. The Category D era started in the 1950s when Brandon and Byshottles built houses in the Brandon Collery area, near Browney, Littleburn and old houses in Langley Moor. Houses were pulled down in Whitwell Terrace, Brandon Lane, Front Street, North Brancepeth Terrace, Angus Street, Lynas Street and some in North & South Street that were front & back with a passage for front tenants to go to outside to the closet and coal house. Taps were fitted, water carried through the passage to a sink in rear yard. Most on High Street North were like this. My parents were in business until 1963 at 74 High Street, Langley Moor. No. 74 is still there, now taken over by the domestic cleaners and laundry. Many people took a long time to get used to being in Brandon, Some got settled in Meadowfield Estate. Now Brancepeth had prefabs build, and later more council houses. Many liked the prefabs, but had to leave as I think they deteriorated. More houses were built on Saw Mill Estate when Brandon & Byshottles Council bought the yard at the auction sale in 1950s. |

history group |

|

|

Leading up to 1970/71, when you went into any of the shops in Langley Moor, the main topic of conversation was whose house was coming down and whose wasn’t. You couldn’t miss it, even if you went straight in and out of the shops. People just didn’t want to leave Langley Moor and be moved to Brandon. I remember High Street North from Walter Wilson’s shop up to the Salvation Army was knocked down. Above the Salvation Army, another 2 houses were knocked down. It was very strange seeing the remaining walls with, in some cases, the wallpaper sometimes peeling off. With all the rubble lying about it looked like a scene from the war. It was also strange to be able to see the allotments through the gaps. |

history group |

|

|

These are my memories of the Cooperative Store at Meadowfield from growing up in the village. I suppose the Co-op was a kind of department store. Built in the late 1890s, this building would have been quite impressive for a small place like Meadowfield. Affectionately known as ‘the store’ by locals, the co-op catered for everyone and everything and the generous dividend payments it made to its customers kept them returning, and it was a really welcome token. Before I enter the Co-op at the main door I will turn left and take you down to the very end of the building where customers entered for the cinema (known as ‘The Hall’). Up the stairs the cinema was on the first floor. After the film, a customer could exit by one of the two doors, either down the outside wooden stairs to the ground level or through the big double doors and down the main staircase to the street. Behind the wooden steps on ground level was the abattoir, the slaughterhouse. On the first floor were the offices and you could purchase carpets, furniture, ladies’ and childrens’ wear as well as household good there. Down the staircase would bring you to the ground level where you would find the Grocery Department, the Butcher, men’s wear and tailoring, the boot and shoe department and the shoe repairs. Outside the Co-op to the left were the Co-op stables, I believe. The Co-op also had a mobile grocery van. I can remember it calling at my grandmother’s every Saturday lunchtime. |

history group |

|

|

This is written from the view of a child/young adult. I was too young to be actively involved. After the Great Depression and the Second World War, Durham County Council was concerned by the decline in the heavy industries which had traditionally provided employment for the area. One solution to this problem was the introduction of industrial estates, and monetary inducements to businesses to re-locate to the county. To staff these new centres of industry, there would need to be new housing near the industrial estates, as well as a new infrastructure of roads etc. At the time it was noted that much of the existing housing stock was substandard, and the council carried out an assessment of housing need. In order to ensure correct future provision of housing and support systems (medical centres, schools and such), the council put every town and village into four categories: Category A – where considerable investment would take place to cater for a future increase in population Category B – where the population was expected to remain stable, and there would be adequate investment to sustain it Category C – where there would be only sufficient investment to cater for a reduced population Category D – where there would be no further capital investment as a considerable loss of population was expected From my earliest childhood, I was aware that Langley Moor was in Category D. I actually thought that D was short for demolition. I was too young to know what would happen to the village, but I knew that my mother was deeply unhappy. Although the County Development Plan 1951 stated that ‘there is no proposal to demolish any village, nor is there a policy against genuine village life’, mam knew that it was the council’s intention to clear Langley Moor, and to relocate the villagers to Brandon. Mam was very loyal to Langley Moor; it was where her family and friends lived, where I went to school, where mam shopped and worked. In those days, there was inter-village rivalry, with the young lads fighting each other, and the adults generally staying within their own locality. It is difficult to understand how the ‘Powers That Be’ believed that people would be easily manipulated into forming new communities from residents from different areas. It was against this background that we began our almost nomadic existence, moving from house to house (slum to slum!) to avoid being rehoused to Brandon. There were no improvement grants for the run-down streets, and landlords would not invest capital in buildings awaiting demolition, so the conditions were grim. Even the local primary school suffered from lack of investment in its buildings. The houses we lived in, whether in Angus Street, Jubilee Terrace or the High Street had outside toilets, one even had an ash midden. There was no hot water, and in many cases only a cold water tap above a bucket to catch the drips of water. There was no kitchen, only a pantry, and a tin bath hanging on a nail in the yard. Mam cooked on top of the coal fire, though we did at one point get a Baby Belling mini electric cooker! We were overcrowded - in my earliest memories five people slept in one bedroom. But despite this, we were happy. I was not aware that we were poor – wasn’t everyone else the same as us? It was only when I went to Wolsingham Grammar School and made friends with children from various backgrounds that I realised how little we had. Mam didn’t want me to bring my new friends home, she was obviously ashamed of these houses, with their outside toilets and black lead fireplaces. So I would stay at other peoples’ homes, they would never come to stay at mine. While I was growing up, mam saw a lot of Peggy Halliday, who would become an Independent councillor, fighting the abolition of the Category D label. I have fond memories of Peggy, who was passionate about saving the village. She was joined by two other Independents, Mr Gravelin who lived in Black Road, and Mr Tonge, and the three of them gained seats on Brandon and Byshottles Urban Council East Ward in 1961. Eventually, Walter Stobbs, a local butcher whose home and business were lost to demolition, also became a councillor. All of this political activity must have given mam hope for the future, especially as some villages were reprieved. When I got married in 1970, we bought a house in Waterhouses, which we got very cheaply as it was also due to be demolished. However, a neighbour who was a councillor’s son began rewiring and replastering, so we surmised that Category D was due to be lifted. The house is still standing today, over 40 years later! Eventually, ill health forced mam into becoming a tenant in Brandon in 1980, and she spent the last two years of her life living apart from her beloved home village. I was saddened to see council bungalows being built in Langley Moor just months after her death. She would have loved a brand new home with all mod cons beside neighbours she had known all of her life. |

history group |

|

|

At Brandon, a group of over 60s met at the Youth Centre over a period of about twelve weeks. They used pictures from the Britain From Above collection to stimulate interest in their own local history. The youth club is situated in the new Brandon village, but many of the over 60s remember the old houses and shops of Brandon Colliery, Langley Moor and Meadowfield. Many people from the older villages were re-housed in the newly-built Brandon in the 1960s - the old villages had been designated Category D by the County Council in 1951, as part of their County Development Plan. But as you will see from the photographs, much of Langley Moor and Meadowfield were not demolished, and only Brandon Colliery was largely rebuilt. Young people from the Youth Club were interested to find out about the old houses and where the colliery had been. They had a walk around the area to find this out, and they photographed Brandon and Meadowfield as they look today. They also interviewed some of the over 60s group to find out what it was like to grow up in the area when they were children and teenagers. The young people photographed the Miners’ Gala in 2012, and the older people used these photos to think about and record their memories of Gala Day. The young people and the over 60s went on a trip together to Beamish Resource Centre and Museum, where they were able to look at a miners’ banner close up, and see and handle museum objects which the older people could help to interpret. Some of the group went into the museum while the rest enjoyed using the photo archive to look at old photos of Brandon and surrounding villages. During the project, the over 60s also wrote down some of their memories, and we have added a selection of these here. One of the themes of the Britain From Above collection of images is the changing nature of housing. Although the new houses had bathrooms and gardens, many people missed the community life of the old streets. The Miners’ Gala celebrates the mining heritage and the community spirit which went with it. Dorothy Hamilton |

history group |

It was the highlight of the year. We made skirts tops and had shoes the same so we all looked the same. We were up early, then ran across the fields from New Brancepeth to Ushaw Moor to catch the train into the city. It was usually the same trains as the banner.

Once in Durham, we would line up in front of the banner and band, then we danced from side to side in a line to the race course. Progress was slow as there were so many other bands and lots of people. The bands always stopped and played outside of the Royal County Hotel as the politicians and union leaders stood on the balcony.

My mam and her sisters always met on the steps of the Bethel chapel which was where Iceland is today. My Father who was an invalid went as long as he was able and sat beside the New Brancepeth banner on the racecourse.

Beryl